Why a small phase may decide a planet’s fate

A new peer‑reviewed study argues that a seemingly minor phase in planet formation may steer the long‑term destinies of rocky worlds. In the inner Solar System, high temperatures let iron and silicates condense, seeding Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars with dense, rocky material while stellar winds swept away much of the gas. Yet despite common origins, these four planets diverged dramatically, hinting that another crucial factor was at play.

The researchers spotlight the epoch known as late accretion, a period after the bulk growth of planets when smaller bodies continued to collide with them. Terrestrial worlds gained roughly 99% of their mass within 60–100 million years, but the final ~1% arrived in sporadic impacts that packed extraordinary punch. Those late blows, though relatively rare, could have reshaped interiors, crusts, and atmospheres in far‑reaching ways.

The overlooked 1% with outsized consequences

Think of late accretion as the final strokes of a planetary portrait: subtle, but decisive. Each impact delivered energy, metals, and volatiles at different times and places, potentially resetting mantle convection, crustal thickness, or atmospheric retention. Because timing governs cooling state, magnetic field strength, and surface conditions, the same mass of impactors can yield very different outcomes.

Crucially, these collisions were not uniform in frequency or severity among the four terrestrial planets. Some worlds faced a handful of giants, while others absorbed a sequence of moderate blows spaced out over tens of millions of years. That variability would naturally imprint distinct interiors and surface expressions such as volcanism, tectonics, and topography.

Four worlds, four late‑collision stories

-

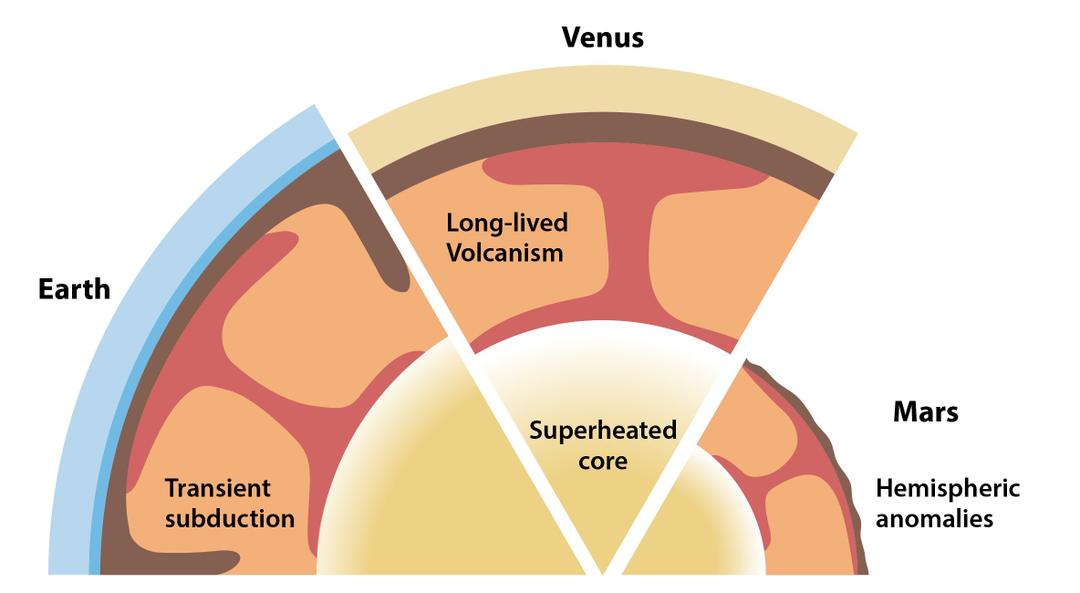

Mercury: A major late impact may have stripped much of its mantle, leaving an outsized iron core and a thin rocky shell. Such an event neatly explains Mercury’s density and magnetic history.

-

Venus: A series of energetic collisions could have kept the interior hot, sustaining vigorous mantle upwelling and rampant volcanism that may persist today. Prolonged heat would hinder plate tectonics from taking hold.

-

Earth: More moderate, well‑timed impacts may have nudged transient plate tectonics into motion, jump‑starting a grand geochemical cycle. That cycle, coupled with surface water, stabilized climate and fostered life.

- Mars: A late, massive collision could explain its stark hemispheric dichotomy, with the northern lowlands and southern highlands recording a violent asymmetry. Such a blow would also influence volcanic and thermal evolution.

Atmospheres on the edge

Late impacts can both erase and enrich atmospheres, depending on size, speed, and entry angle of the impactors. A single giant collision can blow off a nascent envelope, while a gentler bombardment can deliver water and other volatiles that build pressure and enable surface liquids. The sequence matters because an atmosphere’s fate depends on thermal escape, magnetic shielding, and interior outgassing happening on overlapping timescales.

On Venus, sustained heating and outgassing appear to have fed a thick, greenhouse atmosphere, whereas Mars’s smaller gravity and early cooling left it vulnerable to loss. Earth likely threaded a narrow path, retaining enough volatiles while avoiding sterilizing blows, allowing oceans, clouds, and a temperate climate to persist.

“As the authors put it, late accretion is the small tail that wags the big dog, turning modest impacts into major planetary outcomes.”

A new guide for reading distant worlds

These findings offer a practical lens for interpreting the bewildering variety of exoplanets. Two Earth‑sized worlds in similar orbits could diverge radically if their late collision histories differ, producing one tectonically active, ocean‑bearing planet and another stagnant, ultradry hothouse. Remote observations of density, thermal emission, and atmospheric composition should be read alongside models of late bombardment.

Future missions and telescopes can search for indirect signatures of divergent late histories. Scientists will look for:

- Anomalous core‑to‑mantle ratios suggesting mantle stripping by giant impacts.

- Volatile abundances that imply delivery versus loss during bombardment.

- Surface heat‑flow and volcanic activity consistent with prolonged internal heating.

- Tectonic or crustal patterns hinting at transient or sustained plate motions.

By foregrounding the final 1% of growth, the study reframes how we assess planetary habitability. Instead of asking only where a world formed, we must ask how its last impacts landed, when they occurred, and what they carried or removed. In that closing chapter of assembly, a few well‑placed strikes may have written the endings we see across our Solar System—and the countless variations unfolding among distant stars.